Tibetan Plateau

A Glimpse into Tibetan Customs

1-31 Writer

Note: This month, we will occasionally post additional extended content on our Facebook page on Mission Days. If you see a small FB icon next to the title, feel free to visit our page to view the supplemental post.

Tibetan Customs

Listening to the Breath of Another World

The world is vast, and the ways humans live are wonderfully diverse. As we explore the customs of Tibet, we may encounter practices that seem astonishing or unfamiliar. Yet, as anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss observed during his fieldwork in the Amazon, many cultures that appear “backward” or “superstitious” through the lens of modern society are, in fact, simply different in how they think and organize social life. Every culture represents a people’s thoughtful response to their circumstances—a choice shaped by reflection and experience, with its own internal logic and system of understanding.

Lévi-Strauss’s insight reminds us to set aside notions of “progress” and “primitiveness,” to appreciate the rich diversity of humanity, and to seek the shared human spirit that connects us all. From understanding comes gentleness—and from gentleness, true respect.

Tibetan Religion and Festivals

Moments of Joy on the Roof of the World

Across the vast and silent skies of the Tibetan plateau, people live scattered among the winds and snows, each family dwelling in its own solitude. But when festival days arrive, laughter breaks through the stillness. Hand in hand, they join the circle of the Guozhuang dance, rekindling a deep sense of unity and belonging. No temple bells are needed—Tibetans from near and far seem to gather as if by shared instinct. These moments of celebration flash like sparks against the weight of daily toil—brief but bright, fulfilling the heart’s twin longing: reverence for the divine and warmth in human fellowship.

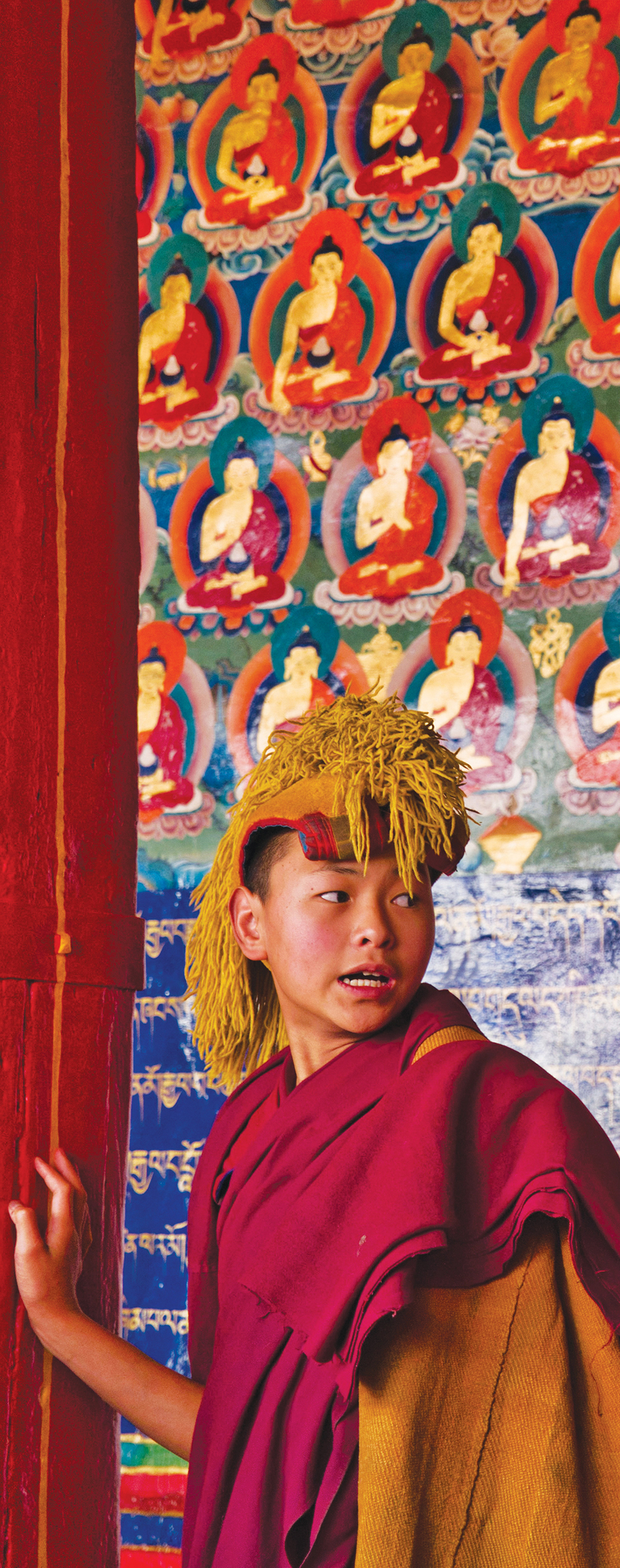

Shoton Festival

During the summer months, when plants and insects flourish, Tibetan monks observe a three-month retreat known as the Buddhist “Rains Retreat,” staying indoors to avoid harming living things. On the 30th day of the sixth lunar month, the monks emerge, and the faithful gather to welcome them with offerings of yogurt—hence the name Shoton, “yogurt festival.” Mothers bring hand-sewn clothes and socks to their sons who are monks, while the day bursts into color with Tibetan opera (cham), folk games, and lively marketplaces.

Thangka Unveiling Festival

At Drepung Monastery near Lhasa, the Shoton Festival reaches its peak with the dramatic unveiling of a colossal thangka—seventeen stories tall and stretching 60 by 47 meters. Over a hundred monks work in unison to carry and unfurl the sacred image, allowing both sunlight and devotion to fall upon it. Pilgrims flood the hillside to witness the moment when sunlight bathes the image of the Buddha, much like crowds gathering beneath the Taipei 101 tower on New Year’s Eve.

Editor’s Note: Each monastery observes its own Thangka Unveiling date.

Butter Lamp Festival

On the fifteenth day of the first lunar month, Kumbum Monastery glows with butter sculptures—intricate creations of birds, beasts, flowers, deities, and entire story scenes, all modeled from yak butter. Hundreds of butter lamps surround them, flickering gently in the cold night air—Tibet’s own version of the Lantern Festival. Young monks hurry about with oil pots, carefully refilling the lamps so every detail of the butter art can shine through the night.

Editor’s Note: Butter sculptures—offerings said to have begun when monks shaped flowers that would never fade—are, along with mural painting and appliqué embroidery, among Kumbum Monastery’s three great arts.

Tibetan Farming and Herding

Bells on the Pastures × Songs in the Valleys

In Guns, Germs, and Steel, Jared Diamond notes that one of the keys to humanity’s ability to settle, develop technology, and raise larger families lies in agriculture and animal husbandry. Yet to sustain such a way of life, land and people alone are not enough—what’s needed are animals that can be domesticated and crops that can thrive.

Come and explore the grasslands and river valleys that sustain Tibetan life, where people live in harmony with the plants and animals they have tamed. Scholars have discovered that Tibetans carry a strand of DNA inherited from an extinct ancient human species, allowing them to resist altitude sickness and adapt to low-oxygen environments with remarkable efficiency. But another secret behind their survival—one that helped them build settlements high above the clouds, from 2,500 to 5,000 meters—lies in something surprisingly small: a seed?.

Tibetan Art and Culture

The Art of Regong

Europe has its Michelangelo, Rodin, and Notre-Dame Cathedral; Tibet, too, has its own masters—the artisans of Regong—whose brushes and chisels have shaped the spiritual imagination of the plateau.

In the northeastern corner of the Tibetan Plateau, where the Yellow River curves in its first great bend, flows the serene Longwu River through a city called Tongren—known in Tibetan as Regong, meaning “the golden valley.” From this place emerged Regong Art, the heart of Tibetan aesthetics. Its thangkas radiate sacred beauty; its applique embroidery glows with layered texture; its carvings and temple architecture reveal devotion in every curve and color.

Regong art began as a monastic craft—holy work passed down within the monasteries of five villages in Tongren. In those days, nearly every household had a son who took vows, and once ordained, he apprenticed under a master painter or carver. Each stroke of the brush, each carving of the blade, was both worship and discipline. These monasteries became “schools of sacred art,” nurturing generations of craftsmen whose hands carried quiet brilliance.

Today, Regong artisans travel far beyond their valley—to Tibet, Mongolia, India, and Nepal—adorning temples with their intricate work: sanctuaries and altars, beams and pillars, doors and eaves, ceilings and cornices. They pause for hours to perfect a single gaze of the Buddha; they labor for days to carve the hidden beauty of a ceiling no one may ever see.

Let us enter these artistic villages in spirit, to glimpse the “Michelangelos of Tibet”—and to pray for these artists and their communities, long immersed in a world of religious imagery, that they may come to know the true Creator whose glory surpasses every work of human hands.

Faces of Tibet

More Than You Think

Not every Tibetan lives amid Lhasa’s temple spires or the sweeping grasslands filled with yaks. Some make their homes deep in the mountains of western Sichuan. Some spend their lives tending salt fields, living in rhythm with the wind and sun. Some wear crosses and worship Christ. Some dig not for cordyceps but for lingzhi mushrooms. Others don white prayer caps, working the markets by day and turning toward Mecca in prayer. And some—are not in Tibet at all.

Tibetan culture rises and falls like the mountain ridges themselves—diverse in landscape, language, faith, and way of life. Across this vast land are many extraordinary faces, each revealing a story waiting to be found.

The Ecology of Tibet

Signs of Life Above the Clouds

Names like Chinghai Hoh Xil and the Changtang Nature Reserve sound distant and mysterious. These are lands where the world begins above 4,500 meters, an altitude where oxygen is barely 40% of what it is at sea level, and every human breath feels like a challenge.

The plateau’s moods shift without warning: four seasons can pass in a single day. One moment the sky is brilliant and still; the next, snow whirls out of nowhere. Yet in this place where human life struggles to endure, Tibetan antelopes leap effortlessly, wild yaks roam with steady pride, and snow leopards slip like shadows across the ridges. Here, in the thin air, rare and hardy creatures mate, bear young, and keep life going on the roof of the world.

This wilderness once captured the lifelong fascination of the renowned biologist George Schaller, who returned here year after year. His research and advocacy led to the creation of the Changtang Nature Reserve, which put an end to large-scale poaching of Tibetan antelope.

But even this land, so far removed from civilization, has not escaped the reach of climate change. Wetlands are drying up; grasslands shrink by 3–5% each year. The shallow roots of alpine meadows can no longer hold the soil, and fierce dust storms rise from the barren ground.

And yet, astonishingly, even in this so-called “forbidden zone of life,” people remain. Who are they? What stories lie behind their endurance? In the days ahead, our prayers will climb these high mountains—seeking traces of life hidden in the wind and snow.