Algeria

|

Green on the flag symbolizes Islam, while white stands for purity. |

| 2.38 mililion km2 | 46.16 million | ||

| Algiers | Dinar (DZD) | ||

| Arabic and Tamazight (official); French is widely used in business and media. | |||

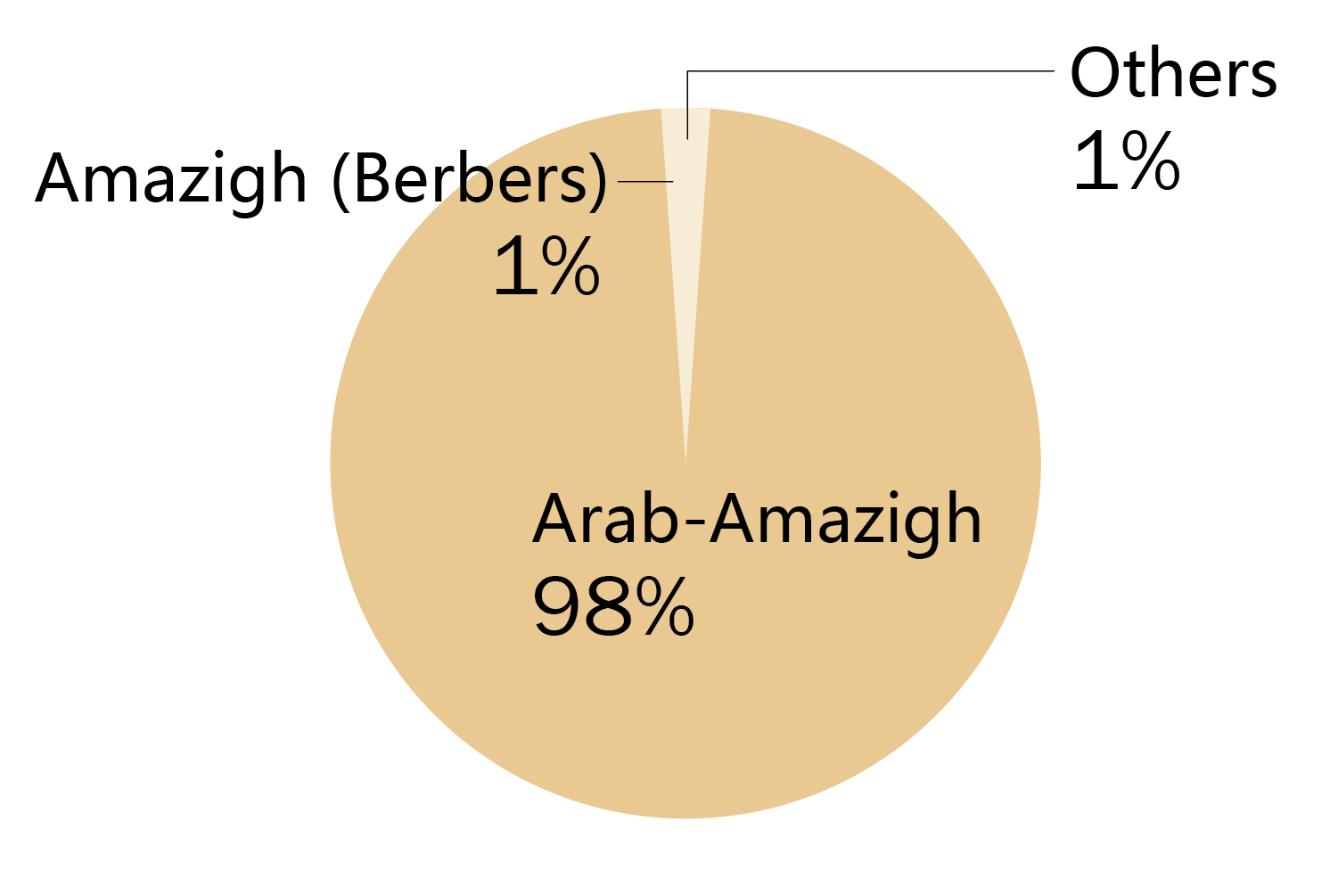

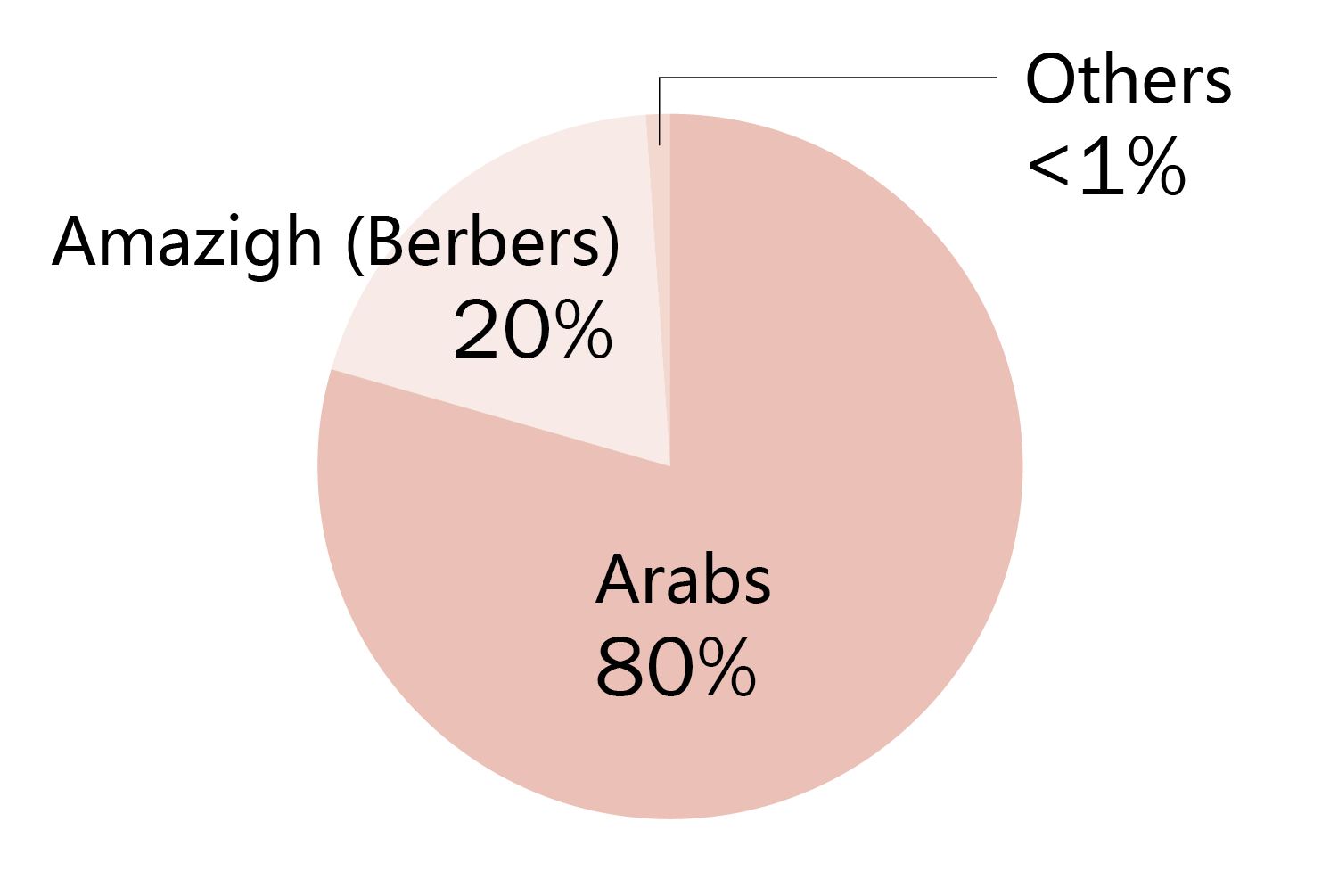

The Amazigh include Kabyles, Shawiya/Chaoui, Mozabites, and Tuareg. Algeria also has small populations of Saharawi, Black Algerians, and migrants from sub- Saharan Africa.

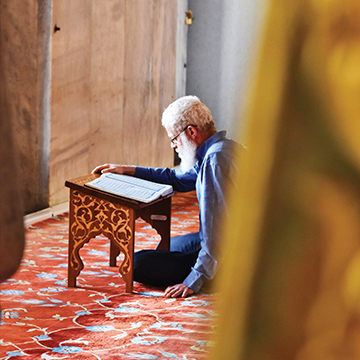

| 99% | Sunni Islam |

| 0.4% | Christianity |

| 0.4% | Atheism/Agnosticism |

| 0.2% | Other (Baháʼí, Judaism, Ahmadiyya) |

|

The vast majority of Algerians are Sunni Muslims. Christians make up less than 1% of the population. Christianity disappeared by the 9th century, and by the 12th century, no Christians or churches remained. |

Sources: World Bank, Statista (2023)

Algeria’s economy remains heavily dependent on natural gas and oil, and diversifying its economic base has long been a central government priority. Its main trading partners for both imports and exports are France, Italy, Spain, and China.